Book Review: Apocalyptic Planet by Craig Childs

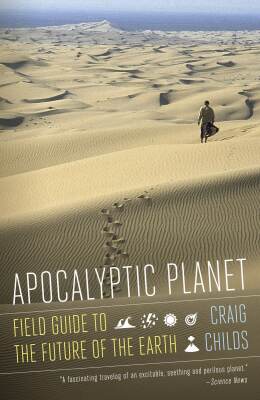

I’m a fan of adventure science writer Craig Childs. Each of his books—Secret Knowledge of Water, Soul of Nowhere —I’ve carried in a backpack and read mostly by headlamp light, in many of the desert southwest wildernesses he writes about. But Apocalyptic Planet sat on my shelf for years, because I didn’t care for the subtitle. Field Guide to the Future of the Earth sounded resigned to an apocalypse, so I stubbornly left it there to languish, Orion Book Award Winner or not. I finally got around to it one chilly afternoon in a soggy tent in Arizona, a few miles from the Mexican border, as gentle winter rain pattered and surged outside. The first chapter, “Deserts Consume,” is set in the enormous sand dune expanse of the Gran Desierto of Sonora, Mexico, southwest of our camp just beyond a jagged range of dark granite mountains.

This part of the Sonoran Desert is particularly arid, with two to three inches of annual rainfall. The Sierra El Rosario mountain range of the Gran Desierto is the driest mountain range in North America. Childs and his travelling companion crossed the dunes, still sweltering even in autumn, from one of their water caches to another. It’s not a trip I would have enjoyed; sand everywhere, in ears, eyes, noses, grinding between teeth, but this is part of what makes Childs’ work so interesting—a willingness to personally endure hardships that most people wouldn’t, for the sake of exploring deep and distant outbacks. To cope with midday heat, for example, they buried themselves in sand and suffered the hours out, shaded only by their sarongs. Not the sort of ordeal many would choose.

El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve, Sonora, Mexico

By choice or not, we are experiencing steady desertification of the world by agriculture and a warming, carbon-laden atmosphere, and it will get worse without significant intervention. Childs quotes paleoclimatologist Peter Fawcett and colleagues, “Models of climate response to anthropogenic warming predict future dust-bowl-like conditions that will last much longer than historical droughts and have a different underlying cause, a poleward expansion of the subtropical dry zones.” Childs adds, “Dear Arizona: Mexico is coming.”

Climate models also predict that oceans will continue to rise as the major remaining ice sheets melt. Childs explores the rising seas on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, where mammoths and Ice Age humans once wandered the Bering Land Bridge and the Bering Sea continues to creep upward, flooding out the Yup’ik indigenous people.

Some of the changes Apocalyptic Planet chronicles are ordinary fluctuations of climate and geology that have been a part of Earth’s history since its beginning, and some are wholly the product of industrialization, the process of rendering life into commodities. Childs visits fresh lava fields in Hawai’i, but also takes a hellish summer backpacking trip in an Iowa cornfield devoid of virtually all life but corn, topsoil long since spent, nothing but chemical enslavement of genetically modified crops.

He observes dramatic ice erosion at the Northern Patagonian Ice Field of Chile, which has lost 30 cubic kilometers of ice every year since 2002 to enormous avalanches of ice and sudden violent floods of meltwater. Camped near an eroding ice field one night, he’s startled awake by “what sounded like a volley of artillery fire” but is actually a falling serac, a block of glacial ice. While seracs routinely cleave from glaciers, the present scale of loss is far from routine, as the book emphasizes throughout. “Nearly all equatorial glaciers that were numerous a century ago are now missing. You can clearly say something big is happening, a warming, an acceleration, an ending of a time.”

Conversely, in the chapter “Cold Returns,” Childs argues that “In the future, there will be ice. Lots of ice….Whether this happens in thousands of years or millions, it will happen.” He joins an expedition to the west coast of Greenland with a team of ice-climate scientists to see what life was like on the planet during a phase of long brutal winters, very short summers, and ice everywhere, thick, massive, and advancing. Anthropogenic warming is reversing the nearly 50-million year planetary cooling trend, but may paradoxically disrupt regional climates.

The melting Greenland ice sheet could dilute the northern Atlantic Ocean enough to change the trajectory of the Gulf Stream. If so, Europe will be in for some long winters. Other effects of resource extraction and consumption that once seemed far-fetched are emerging as well: earthquakes caused by fracking and waste injection wells, hurricanes driven by a warming atmosphere and ocean, the ocean itself acidifying from the absorption of carbon dioxide. No one can possibly predict the outcome of tampering with such a complex system, other than that there will surely be consequences.

How to avoid them? Apocalyptic Planet doesn’t get into this much, and when it does, the remedies are hopelessly inadequate. Childs quotes a geophysics and climatology professor, “I guarantee you there are millions of solutions. Here is a simple one: increase the efficiency of automobiles.” While this might be technically possible (though unlikely), it’s still far from a real fix. If we allow oil companies to extract the approximately 1.5 trillion barrels of oil still in the ground, it won’t matter much if we burn it in the projected 47 years, or 100 years. The effect on climate will be nearly the same. Postponing a problem is no solution. Like almost everyone else, most scientists take industrialization as the given, as synonymous with humanity, and not the recent experiment that it is—the very problem itself. Industrialization is rendering the planet uninhabitable; it’s the constant in the equation that makes every environmental win temporary. Save a forest with a lawsuit, lose it to drought. Save the whales from commercial hunting, lose them to plastic garbage.

Of the dissolving of the ice fields Childs writes, “I’d stop it here if I could. I have a particular fondness for this kind of earth…the Holocene where we are somewhere between ice and not.” Childs doesn’t ask, but how to stop the loss? is the question, the only one that really matters. Is reversing global warming within our ability? I think it is—and it would be fairly simple. We probably can’t stop a meteor from striking the earth, but a few thousand well-trained, well-organized people could stop the flow of oil, thus stopping a great majority of the destruction of the planet. Humans could rebuild topsoil with grazing herbivores, and restore forests on a scale that could meaningfully reduce atmospheric carbon. They could also insist on absolute political and social emancipation of women and girls, ensure their literacy, and promote free family planning—a proven way to quickly and humanely reduce the human population, as Iran did from the late 1980s up to 2014, when the policy was tragically reversed.

Most of these are politically difficult objectives, to say the least. Those who wield the actual power in our time, the financial and political elites, will never agree to them because the business of consuming the earth—oil, coal, topsoil, human labor—is simply too profitable. The consumer class is completely reliant on industry for every aspect of their working and leisure lives. Agriculture has made us a race of toiling dependents, and corporate capitalism has welded us to the ever-declining trajectory of the industrial age. Virtually no one questions this foundation of our lives.

Yet it all will end eventually. Fertilizers synthesized from natural gas and mined minerals are, like oil and coal, a finite resource. It doesn’t take much imagination to foresee what will happen when—not if—these indispensable feedstocks for industrial humans and their way of life run out. Will our time here end with every drop of oil burned, every acre covered with cornfields and wind farms? Will humanity’s conclusion be biodiversity’s ruin? 10 billion humans driven to extinction on a planet unable to support complex life? Or will the flow of oil be stopped preemptively, against the will of eight billion humans, but leaving them a chance to transition to localized, lasting cultures based on the gifts and needs of their land?

Back to my Arizona winter camp. The storm finally cleared so I set Apocalyptic Planet aside and my companion and I took a long walk. The damp Sonoran Desert smelled sweetly of Larrea tridentata, the abundant green creosote bush. Saguaro cacti, tall and spiny with comically waving arms, a southwest icon, were plump and happy, each filled with tons of rainwater. Along the eroding foothills birdsong rang out; rolling valleys of decomposed granite alive with everything that three inches of rain a year will allow. All seemed content and engorged. Everywhere we looked, in secret grottoes, distant canyons, and under the sprawling limbs of exotic elephant and ironwood trees, life flourished. Wood rat nests mounded under cholla cactus thickets, and wolf spider dens and rodent holes punctuated coarse granulated soil. Tracks of scampering small mammals, lizards, and desert bighorn sheep unspooled like arcane petroglyphs.

In the hypnotic heat of summer, rattlesnakes coil in the shade of gray-leafed brittlebush, male tarantulas prowl the moonlight for suitable mates, and red cardinals perch in palo verde trees, startling red like Christmas tree ornaments. All relatively safe, for this World War II-era bombing range is now marginally protected by its National Wildlife Refuge status, its 110 degree plus days, and by its remoteness and lack of appeal to most everyone but the occasional sheep hunter, and desert disciples like us.

Yet as we walked along the Mexico border, looking with rapt interest into the secret peaks and valleys of the Sierra El Choclo Duro—Mountains of Hard Corn—we could not help but remember that the small border fence was to be replaced by Donald Trump’s towering steel wall. Even the most distant and inhospitable places, which we’d forlornly hoped were of no interest to anyone, are not safe from violation. The border wall recently advanced across supposedly protected land and places sacred to the indigenous Tohono O’odham people. It doesn’t matter if the wall, or anything else, is illegal—so long as those in power have the ability to do what they want, they will do it, and the only way to stop them is to permanently disable them. So again, the critical question: how?

Apocalypse is not an inevitable outcome. If we are to save the Goldilocks climate of the Holocene, and if we are to preserve any chance of a decent and dignified future for humanity, the answer to that critical question—how to stop the forces of destruction? —must begin with stopping fossil fuels. We’re researching and sharing effective strategies and tactics to shut down the flows. Learn more in our how to stop fossil fuels overview, and by subscribing to our mailing list below.

Consider supporting our work by joining our mailing list below, sharing & "liking" this page, and following us on social media. You may freely republish this Creative Commons licensed article with attribution and a link to the original.