Why stop fossil fuels?

Our future: wasteland or life?

Climate change is already increasing the frequency and/or severity of fires, floods, droughts, and hurricanes. Sea levels have risen 8" with more to come. Ocean acidity has increased 30%, and coral reefs worldwide are suffering unprecedented bleaching. From 2008 to 2017, 21.3 million people each year were displaced by climate and weather-related disasters, and perhaps hundreds of millions will be climate refugees by 2050. The devastation we’re experiencing today results from only 1°C of global warming since the 1800s. Scientists argued decades ago that limiting the increase to 1°C was the safest option, but that was considered infeasible. The Paris Agreement aims for “well below” an arbitrarily chosen 2°C, and professes it still feasible to keep warming below 1.5°C. Pretenses of politicians aside, we’ve already locked in an increase of 1.5 to 2°C even if we stop burning all fossil fuels tomorrow: Conditions, already dangerous for hundreds of millions of people, will inevitably worsen. We simply can’t afford to burn any more carbon. We have a practical and moral imperative to stop fossil fuels now.Climate change is wreaking devastation now, and will get much worse. The idea of a “carbon budget” for the coming decades is delusional; we’re already deep in carbon debt.

Industral pollution—air, chemical, soil, and occupational—killed 5.5 million humans in 2015, a rate increasing an average 50,000 per year since 1990. (Lancet Commission on pollution and health, figure 7) As of 2012, climate disruption killed 400,000 humans each year. Projections are for nearly 700,000 deaths per year by 2030. (DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor, 2nd ed)Fossil fuel pollution and climate disruption kill humans: more than 6 million annually, and climbing rapidly.

Fossil fuels destroy landbases at every stage: from extraction to processing to transportation to use to polluting aftereffects. Massive equipment rips open the ground, leaving behind Appalachian streams buried in the exploded remnants of mountain tops, millions of wells fragmenting habitat, and the hell on earth that is the Alberta tar sands—the largest industrial project on earth. Refineries and gas processing plants pollute their environs. Pipelines routinely spill toxic substances, at over 300 “significant” accidents per year in the US alone. Bayan Obo rare earths mine

Worse than the direct environmental harm is the industrial activity fossil fuels make possible. The world has already lost approximately 80% of primary old growth forest, with another acre of natural forest lost every two seconds. Industrial farming converts complex habitats to monocultures for humans, contributes to massive algae blooms, and erodes topsoil at 10-100 times the replenishment rate. Massive open-pit and strip mines create gaping wounds and festering tailings ponds visible from outer space. Industrial operations vacuum up 80% of annual fish catch, resulting in 84% of ocean fisheries fully exploited, over-exploited or already crashed. These fossil fueled pressures have brought on a sixth mass extinction and biological annihilation. By 2014, Earth had lost on average 60% of vertebrate populations, and probably comparable numbers of insects and plants, compared to an already impoverished 1970 baseline. To stop further loss of the wild, we must stop fossil fuels.We are in the midst of global ecological collapse, caused and enabled by fossil fuels. Forests, prairies, oceans, and the very web of life are in critical condition.

Grassroots environmentalists work hard and fight fiercely for the places and creatures we love. We win important battles here and there, but we’re badly losing the overall war. Despite decades of environmentalism, every ecological community across the world is in decline, and climate disruption threatens each place and species we have been able to protect. We’re losing because we fight defensive battles, with wins temporary but losses permanent. We may stave off one clearcut or development project or pipeline one year, but the profiteers come back the next year, and the next, and the next, until they get what they want. Once the forest is cut, the land bulldozed, the pipeline in place, there’s no undoing the damage. There are relatively few of us, so for every one project we try to block, we have to let many others proceed unopposed. For example, in the US, massive grassroots efforts won temporary delays of the Keystone XL and Dakota Access Pipelines, a combined 2000 miles of planned pipeline expansion. Meanwhile, the US completed 17,000 miles of pipelines from 2009 to 2014, with another 23,000 planned or under construction at the beginning of 2016. Fossil fuels are at the root of the ongoing threats to the places and people we love. The onslaughts won’t stop until we shift from reactionary defensive actions with temporary victories at best, to carefully chosen offensive battles targeting the root problem.Our work is Sisyphean. For each step forward, climate disruption and the industrial economy push us 10 steps back. Whether your passion is an ecological community, an endangered species, or future generations, we must stop fossil fuels to defend those you love.

The movement, hoping to trigger mass adoption of a sane and sustainable way of living, has tried hard to convince individuals to change their values and lifestyles. Though some people have responded to calls for change, they remain a tiny minority. All measures of global sustainability are going in the wrong direction. Decades of environmentalism haven’t even slowed the growth of population, consumption, mining, waste, and atmospheric CO2 concentration; all are increasing relentlessly. Rationally, we know it’s a mistake to burn the carbon sequestered over millions of years. But it’s natural for individuals and for communities, whether human or forest or prairie, to fully utilize available energy and food. Fossil fuels are incredibly dense stores of energy, so it’s unsurprising that we’ve developed a full-on addiction. Although a few individuals may choose to forego the easy energy, the majority will happily burn as much as they can, as long as they can. There’s no evidence of a mass shift in consciousness, and with the world at stake, we can’t afford to pretend otherwise. The only way industrial society will stop burning fossil fuels is if it can no longer get its hands on them.The environmental movement has worked for decades towards mass awakening, yet nearly everything keeps getting worse. We can’t rely on hope that this pattern will suddenly change.

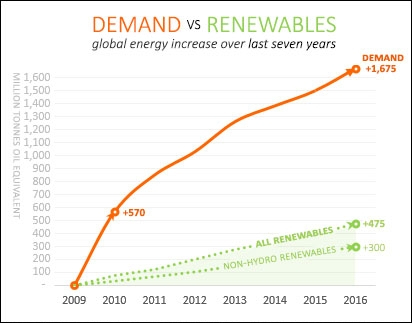

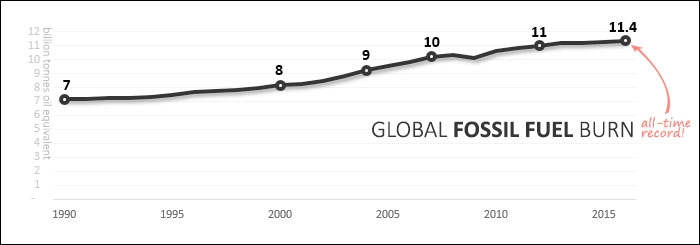

Orange: increase in global energy consumption since 2009. Green: increase in hydropower, wind, solar, biofuels, geothermal & biomass.

Renewables are only a solution if they actually replace fossil fuels, but as Barry Saxifrage elegantly illustrates, “the new business-as-usual is one in which we keep expanding both renewables and fossil fuels at the same time.” Industrial society is responding to ecological and climate crises not as a rational actor in control over its decisions, but instead as an energy addict using as much as it can get, whether clean or dirty. From 2009 to 2016, total world energy consumption increased 15%. New renewables supplied less than 30% of the growth in demand, with the great majority met by fossil fuels. And if you don’t consider hydroelectric dams which kill rivers and displace humans to be “renewable,” then more than 4/5 of the new demand was met by dirty energy. We can’t wait for “enough” renewables to be in place before transitioning; we have neither the time to spare, nor assurance that more renewables will even decrease fossil fuel use. Regardless of how many solar panels and wind turbines are installed, we must proactively stop the burning of fossil fuels as quickly as possible.Renewable energy is growing at unprecedented rates, but isn’t slowing the much faster growth of fossil fuel burn. Green tech is not a solution.

Barry Saxifrage

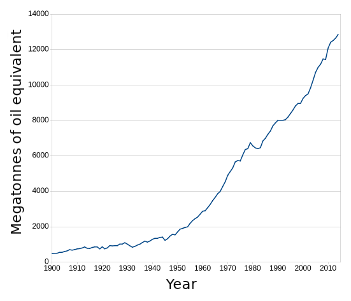

Global energy consumption since 1900

As with green tech, energy efficiency is only a solution if it actually reduces fossil fuel use. A household with a specific need, such as lighting a room each night, will use less electricity with an efficient LED. But because consumer society has unlimited wants, that same lighting technology colonizes clothing, billboards, and entire building surfaces. Not only does this rebound effect negate conservation, but light pollution soars. Unintended consequences undermine all such efficiency measures. Despite the technologies and tricks we developed in the last century, global energy consumption increased exponentially. Clearly, efficiency on its own won’t end our use of fossil fuels. Worse, it may actually amplify their harms, as Richard York illustrates with a simple thought experiment: Imagine two worlds. In one, cars get 50 miles per gallon; in the other, they use 50 gallons to go a single mile. Which world uses more energy? In the world with highly inefficient vehicles, humans would have neither the motive nor the means to build houses distant from work and from shopping malls stocked via global supply chains, all connected by cars, roads, and highways. They would instead build societies optimized for walking and local provision of their needs. Paradoxically, the world with efficient cars gives rise (as we see) to a sprawling network of energy hungry machines. We’re offered efficiency as a way to sidestep fundamental change, but doing “more” while still using every bit of obtainable energy is not a solution. Ending the use of fossil fuels must be primary; efficiency will then play an important role in transition.Paradoxically, energy efficiency increases fossil fuel use. Getting more bang for the buck increases incentive to use resources.

The Shift Project Data Portal

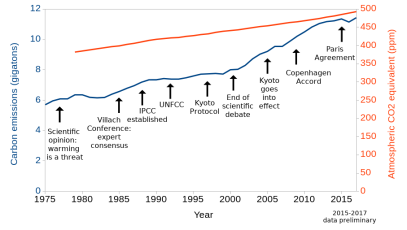

Governmental inaction as carbon mounts up

Through decades of scientific warnings about the dangers of climate disruption, governments have excelled at forming bodies with official names, holding meetings, encouraging more research, and proudly announcing symbolic agreements. Yet somehow, they haven’t actually cut carbon emissions. Not only did they fail to adopt the precautionary principle as scientists debated just how big a problem global warming could be, but they didn’t take meaningful action even after scientific consensus made clear the looming catastrophe. The most recent accomplishment, the 2015 Paris Agreement, is non-binding, with hypothetical emissions reductions far in the future. Like under the Copenhagen Accord before it, governments have no legal mandate to do anything substantive. Meanwhile, investors are pouring money into a 30% global expansion of coal power capacity; the smart money doesn’t believe governments will put a halt to burning coal any time soon. We all know that governments take better care of corporations than they do of people. Fossil fuels are the life blood of the industrial economy. We’d be fools to trust that politicians will suddenly decide to do the right thing after all this time. We must shut down fossil fuels ourselves.Governments have yet to take meaningful action to reduce fossil fuel use, and give no indication that they ever will.

NOAA and Global Carbon Budget

We can’t maintain the ever increasing extraction of oil, natural gas, and coal on which our growth economy depends. Once peak oil forces a reduction in energy use, we’ll see an escalated replay of the 2008 global financial crisis—this time permanent—and a concomitant decrease in fossil fuel combustion. Unfortunately, although peak oil will eventually throttle fossil fuel use and collapse industrial activity, it could still be a few years off. In the meantime, every day that we burn fossil fuels, we force the climate deeper into chaos, kill more than 16,000 humans, and drive entire species extinct. We have a responsibility to proactively stop fossil fuels; we can’t sit back and wait for the system to grind to a halt on its own.Fossil fuels are finite resources, so their use will inevitably decline. But peak oil won’t reduce carbon emissions fast enough.

“Collapse” sounds scary, but it simply means rapid simplification of a society, and will actually increase quality of life in the long term. Such simplification is unavoidable; our way of life is unsustainable, its complexity dependent on ever increasing supplies of dense energy. Responding to the myriad problems of globalization, bureaucracy, sprawling infrastructure, and empire, many people are proactively working toward collapse in their efforts to localize food, water, construction, energy, education, economics and decision making. It’s valuable to build the foundations for local structures now, but they won’t gain much traction until the centralized systems are starved of fossil fuels. States actively suppress efforts which threaten to redistribute power. Economic pressures keep most people busy as cogs in the machine, constricting their freedom to explore alternative paths. The lure of shiny trinkets and technological gadgets is difficult to resist until they’re not there. But the knowledge of how to live sustainably is widely available. As flows of fossil fuels slow to a trickle, necessity will marry existing wisdom to new innovations, birthing localized solutions. As Tom Murphy writes, we’ll move into a better future: Expect More: Reading; story-telling; gardening; connection with nature; community; fishing; whittling; lemonade; sitting on the front porch; cross-breezes; seasonal adjustment; blankets; wool socks; sweaters; connection to sunrise/sunset; local governance; mom & pop stores; crafts; goats and chickens; bicycles; train rides; pies cooling on the sill; music; singing and playing musical instruments; rain catchment; canning; craftsmanship; repair; durable goods. Expect Less: Waiting for airplanes; commuting; abstract/meaningless jobs; Wal-Mart; fast food; strip malls; four-car families; climate disruption; dominance of banks; capital gains; disposable junk; junk mail; species extinction; minibar charges; traffic jams; identity theft; freeway noise; advertisements; consumerism; faddish gizmos; cheap plastic crap; outsourcing; industrial effluent; credit card debt.Fossil fuels bring comforts and elegancies to a minority, but at great cost to everyone. Life will be better in a post carbon world.

We’re carrying out an experiment in madness. It would be great if everyone in the world came to our senses: aggressive, proactive, unanimous reduction of consumption and population—a managed crash—might just stave off disaster for ecological and human communities. But that’s not the path we’re choosing. Far from competing to most quickly reduce their annual income to a globally sustainable level, the vast majority of humans, understandably, compete for larger slices of the pie which they hope will keep growing. Far from each family contemplating a sustainable global carrying capacity and charting a path to match it, humans are behaving, naturally, like every other species, reproducing to match their current food supply. Every day, a net 220,000 new humans join the global population. At the same time, fossil fuels undermine the planet’s ability to support even those already here. Industrial development, manufacturing, transportation, farming, fishing, and logging erode topsoil, destabilize the climate, toxify the environment, and collapse populations of fish and wildlife. The sooner we stop fossil fuels, the less we’ll overshoot, thus the less wrenching will be our adjustment.Human population is already in overshoot, and growing. Meanwhile, our impact on global ecology decreases world carrying capacity every day. A crash is inevitable. The sooner we put on the brakes, the gentler the transition.

How to stop fossil fuels

Valve Turners shutting down a pipeline

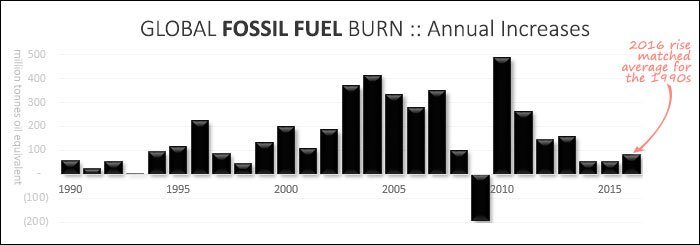

The consequences for humans and non humans are already dire, and getting worse. As a society, we’ve known this for a long time, but haven’t shown an ability to change. The only year in which the world decreased fossil fuel consumption was 2009, the result of global recession. Unless forced into decline by circumstances out of its control, the economy burns more and more every year. The only timely solution is to force decreases. Giving up faith in indirect, sanctioned, false solutions—voluntary mass transformation, governmental action, green tech, energy efficiency—frees our imagination. Our work becomes a relatively straightforward exploration of strategy and tactics to physically stop fossil fuels.Industrial society has had decades to transition voluntarily from fossil fuels and their known hazards, but is too addicted to give them up. It’s time for an intervention: we must physically shut off the flows ourselves.

Asymmetric forces, unsuitable for attrition

Attrition is a protracted slow struggle, with the goal of wearing down the forces of environmental degradation until they cease to function. We react defensively and oppose one destructive project at a time. But we’re losing. Our occasional victories don’t actually weaken the institutions expanding industrialism; at best we’re merely slowing the rate at which they strengthen. To begin winning our campaign of attrition, we’d need not only to block all industrial expansion, but to force closure of existing pipelines, power plants, and oil fields. But even if we achieved that, our strategy would still be a failure. Attrition only works if one grinds down the opponent while limiting one’s own gradual losses to acceptable and sustainable levels. But there’s nothing gradual, acceptable, or sustainable about today’s rising CO2 and declining biodiversity. Catastrophe is imminent. Even if we had the people power to wage a war of attrition, we don’t have the time. At a tactical level too, we rely on attrition: we file lawsuits, boycott and divest from companies, blockade pipelines, and lock down to construction equipment, trying to make a project uneconomical. But multi-billion dollar investments can easily budget to overcome the obstacles we place, especially when corporations and governments can predict our tactics. Our work is the very definition of asymmetric struggle. As individuals and as a movement, we must escalate beyond piecemeal attrition.The environmental movement has been pursuing a strategy of attrition entirely inappropriate against a system with far greater numbers and resources.

Over the centuries, military analysts have derived principles of strategy and tactics. Though our goal of stopping fossil fuels is unique, we can apply what they’ve learned to our own work.

Military historian and strategist Liddell Hart summarizes our work: “It should be the aim of grand strategy to discover and pierce the Achilles’ heel of the opposing government’s power to make war.” “A strategist should think in terms of paralyzing, not of killing.” We needn’t dismantle every factory, destroy every bulldozer, tear up every highway. We just need to paralyze their infrastructure. The war against the planet, against the global majority of humans, and against future generations runs on fossil fuels. To move beyond a strategy of attrition, we must think in terms of systems, flows, nodes, and bottlenecks. We must understand how oil, coal, and gas are extracted, transported, processed, distributed, and burned; and where we can intervene for maximum impact. Cascading failure

Industrial systems withstand the loss of an element or two without experiencing further damage, and quickly repair problems. But these systems are designed for efficiency, not resiliency. When enough critical pieces break at once, the failures cascade through the system like a series of dominoes, causing more and more elements to fail. Impacts increase exponentially the longer disruptions persist. Under the right circumstances, the whole system grinds to a halt. With follow up actions, it may never restart. These are general trends; specific campaigns may vary.To stop fossil fuels in this asymmetric struggle, we must employ a strategy of cascading failure to disrupt a fragile technological system.

Attrition vs Cascading Failure

Characteristic

Attrition

Cascading Failure

Target type

New project in the works

Operational infrastructure

Why target chosen

Immediate damage caused by project

Criticality to the system

Campaign goal

Stop this project

Stop this piece of infrastructure, plus others dependent on it—trigger domino effect

Initiative

Defensive

Offensive

Element of surprise

Minimal

Maximal

Target’s role in system

Any

Bottleneck or interconnected node

Number of targets attacked

One at a time, isolated

Multiple, attacked simultaneously for synergistic effect

Targets available

Many and interchangeable

Few and unique

Tactics

Blockades & occupations

Hit and run

Goal of actions

Delay project completion. Make project uneconomical.

Damage or destroy infrastructure, and delay or prevent repair. Make operations physically impossible.

Duration of disruption

Shorter

Longer

Knowledge of system needed

Limited

Extensive and deep

Skill, planning, & caution needed

Less

More

Actions, resources & people needed

Much more

Much less

Suitability for aboveground actionists

High

Nearly impossible

Suitability for underground actionists

High

High

Risk of consequences for actionists

More, if done openly

Less, if done surreptitiously and carefully

Severity of consequences if caught

Lower

Higher

System response

Reroutes around damage

Disproportionately disrupted

Civil disobedience1 escalates legal opposition such as petitioning, protesting, and filing lawsuits. But governments, corporations, and the general public will never allow protestors to disrupt business as usual to the point of cascading failure. At best, they’ll tolerate attrition until they can disperse the blockade relatively cleanly. One-off direct actions have little if any effect on fossil fuel combustion; the system has enough redundancy and buffering to be unaffected by temporary glitches. For civil disobedience to have material impact, not just symbolic, campaigns must maintain disruptions for days, weeks, or longer. Large numbers of people must participate both on the frontlines and in support roles. Media coverage and public sympathy can raise volunteers, but there’s only so much attention to go around. In the US for example, the Keystone XL and Dakota Access Pipelines became well known, but one hundred other projects are nearly unheard of. The Unist’ot’en Camp in British Columbia demonstrates successful civil disobedience, blocking the bottlenecked path of multiple pipelines for years. Their legal basis for opposition, combined with widespread grassroots sympathy and support, has made it much more difficult for the government to sweep them aside. Occupations of operational infrastructure can be successful in cases where the local community perceives more harm than benefit, as in Beleme, Nigeria, where for months hundreds of people shut down oil fields producing 45,000 barrels per day. Before engaging in civil disobedience, consider whether you may in the future want to work underground towards cascading failure. Carefully read about and contemplate the necessary firewall between aboveground and underground activists. The term “nonviolent direct action,” though similar to “civil disobedience,” also includes ecosabotage with its potential to go beyond attrition. Since “nonviolent direct action” lumps together tactics suitable for distinct strategies, we use “civil disobedience.” ↩︎Civil disobedience has some limited applications. Though they can’t achieve cascading failure, sustained blockades with enough people going beyond the merely symbolic can win some victories of attrition.

Sabotage of DAPL pipeline construction

Civil disobedience has a noble history in social change movements. Law breakers proudly accept the consequences of their actions, hoping to win hearts and minds for the cause. But we’ll never sway the general public to support the necessary 90% cut in fossil fuel use, so we shouldn’t temper effective action for their sake. Actionists who work underground, striking surreptitiously then melting into the night without reprisal, can fully apply the principles of strategy summarized above. Unfortunately, most acts of ecosabotage have been limited to attrition, with targets chosen solely to stop the damage they directly cause, or even for symbolic value. When infrastructure is attacked, it’s only in one place at a time, and the disruption is usually quickly repaired. To shift to a strategy of cascading failure, ecosaboteurs might learn from militant resisters to learn how they target entire systems of infrastructure.Ecosabotage allows activists to take the offensive with a strategy of cascading failure. It leverages limited resources against sprawling, largely unprotected infrastructure.

Militant resistance provides, by far, the most successful examples of inducing cascading failure and stopping fossil fuels. The best comes from the oil drenched Niger Delta, where residents suffer the worst effects of pollution and spills: contaminated air, soil and water make forests, fields, mangroves and rivers unable to support human or nonhuman life. An estimated 11,000 infants die each year due to on-shore oil spills. Despite immense riches made from oil extraction, the general population doesn’t benefit—a large majority of Nigerians live in poverty, with life expectancy nearly the lowest in the world. Decades of nonviolent tactics failed to achieve justice, culminating instead in the Nigerian military regime and Royal Dutch Shell conspiring to execute nine movement leaders in 1995. The resistance movement escalated its tactics in response, by 2006 regularly sabotaging and bombing oil infrastructure and government buildings, kidnapping foreign oil workers for ransom, engaging in guerrilla warfare, and launching surprise attacks using speed boats. Multiple groups have been systematically and accurately selecting targets to completely shut down oil extraction and delay or outright halt repairs. Militant resistance cut Nigerian crude extraction by a sustained 200-800,000 bpd since 2006

The Niger Delta militants have killed oil workers and members of government and corporate militaries. However, rough calculations suggest the militants have saved 500 to 1900 lives per month by shutting down 200,000-800,000 barrels per day of oil extraction, far outweighing the number of lives they’ve taken. Though of course we want to minimize the use of violence, militant resisters are working for the greater good.In the Niger Delta, militant resistance has shuttered 10-40% of the country’s oil extraction since 2006, an impact unmatched in the history of the environmental movement. The militants use violence, but have saved many more lives than they’ve taken.

Critical infrastructure is that on which fossil fuels rely for extraction, transportation, processing, distribution, and combustion. Obvious elements include wells, pipelines, rail lines, roads, storage tanks, refineries, power plants, and ports. Less visible are systems of administration, finance, telecommunications, and just-in-time supply chains. All have vulnerabilities which can be exploited. Civil disobedience, such as blockades of pipeline construction or of active rail lines, can impact a subset of critical infrastructure. Ecosabotage and militancy can reach more targets, with more damaging and longer lasting disruptions. Some attacks require extensive knowledge and skills, but many are simple and accessible to anyone. Militants frequently bomb wells and pipelines. Saboteurs (and the just plain drunk) shoot holes in pipelines with rifles. Monkeywrenchers disrupt rail traffic by damaging rails, connecting them with jumper cables, sabotaging cables, and pouring concrete or felling trees onto tracks. Underground activists cut fiber optic communication cables, topple cell and radio towers, and torch transmitters. Cyberattackers crash corporate computers and industrial equipment.Stopping fossil fuels doesn’t require violence. It does require that we use our limited resources to target critical infrastructure. We must understand industrial systems and their vulnerabilities.

The electric grid underpins every stage of fossil fuel use, from extraction to transportation to processing to combustion. Targeted attacks on the grid could idle coal mining draglines, disable pumping and compressor stations on oil and gas pipelines, halt coal and oil trains, shutter refineries and coal preparation plants, or disrupt project administration. Since electricity can’t easily be stored, grid operators must match supply to demand, second by second. So if, for example, damage to an electric substation were to shut down an industrial park, a power plant somewhere would have to reduce its output or shut down altogether. This would be a win-win for the planet, reducing both industrial activity and carbon emissions. The grid is exposed. Globally, thousands of miles of high voltage transmission lines traverse remote areas, and hundreds of thousands of isolated substations dot landscapes. Saboteurs can disable lines and substations with attacks as simple as shooting with a hunting rifle, as demonstrated by experiments at Operation Circuit Breaker and by the 2013 attack on the Metcalf, California substation. Powerline towers are bombed or toppled, and substations are hit by arsons and cyberattacks. Though the grid is designed to withstand the loss of one major node, sometimes even two, further losses overload remaining equipment. In a textbook example of cascading failure, more and more nodes shut down automatically to avoid damage. Recovery from serious damage is difficult. Replacing high voltage transformers can take up to 18 months, as many are custom manufactured for a specific site and spares are rarely stocked. Transportation of the huge, bulky units is difficult and slow, requiring special equipment and carefully planned routes vulnerable to further disruption.The electric grid is uniquely vulnerable to cascading failure. It may be the most critical infrastructure on which fossil fuels depend.

A group may analyze and select targets at multiple scales before taking action. The group may decide to shut down a particular coal mining site, which might lead them to shut down the site’s electric supply. They may then identify a particular substation to take offline, and may ultimately plan their action around vulnerable transformers in the substation. At each level of analysis, activists identify bottlenecks, elements without which the system can’t function. Obvious bottlenecks are single points of failure, such as the electric supply in this example. Where elements are networked with redundant nodes, activists look for nodes with the highest volume and most connections. United States special operations forces developed the CARVER matrix for target selection: Criticality: How important is the element to the system?

Though their commitment and courage aren’t in doubt, most underground environmental activists to date have chosen targets which are accessible and vulnerable, but neither critical nor difficult to replace. The next wave of environmental activists, serious about being effective, will apply the CARVER matrix to potential targets with the goal of triggering cascading failure. They’ll consider not just the ease of accessing and damaging targets, but also the material impact of successful action. See a US Army example analysis of targeting electric supply: the CARVER matrix.Careful target selection of specific infrastructure is necessary for triggering cascading failures.

Accessibility: How easy is it to get to the element?

Recuperability: How quickly and easily can the system resume functionality after damage to the element?

Vulnerability: How easy is it to damage the element with available tactics and weapons?

Effect: What unwanted side effects may result?

Recognizability: How easy is it to identify the target under adverse conditions, such as a dark rainy night?

From existing military doctrine, we can learn not only principles of strategy, but of tactics and operations. Those of guerrilla combat are particularly relevant to our own asymmetric struggle:Governments and corporations won’t permit us to openly disrupt critical infrastructure. We must use hit and run tactics to induce cascading failure.

Get involved

We need people stopping fossil fuels. Broadly, this requires front line activists, loyalty and material support for those front liners, and dissemination of strategy and tactics.

If you’re in a position to take direct action, the planet desperately needs you. It especially needs people thinking and acting towards cascading failure—people capable of going underground to carry out ecosabotage or militant actions. If you can’t engage in underground attacks, civil disobedience can still be valuable. Though an approach of attrition often limits aboveground campaigns, hitting strategic bottlenecks using smart tactics can win real victories. Perhaps more importantly, aboveground actions provide networking and media opportunities to share the strategy of cascading failure with fellow activists and the public.Front line activists directly stop fossil fuels through civil disobedience, ecosabotage, or militant attacks. We need as many people doing this work as we can get.

At a bare minimum, adopt a motto of “See something, say nothing,” a code of silence around ecosabotage and militancy. Encourage others to do the same. More proactively, give front line activists, especially those working in underground seclusion, the moral courage that comes from community validation. Write and speak out in support of resisters and their actions, especially ecosabotage and militancy. Write letters in solidarity to those imprisoned for taking effective action. Expand the range of tactics considered possible and respectable. Material support not only strengthens resisters’ resolve by demonstrating loyalty, but directly helps their work continue. If you have the means, contribute supplies, food, money, training, transportation, or housing. Anyone can find worthy campaigns of civil disobedience, or if you know and can safely give to underground activists, you can nurture even more effective work. Build safety nets and defense funds for those caught and imprisoned by the legal system.Most of us can’t be on the front lines for perfectly valid reasons. But we can all provide loyalty and material support to those doing the necessary work.

The strategy of cascading failure is used by militaries around the world for the simple reason that it works. But nearly no one in the environmental movement has heard of it. It’s up to us to change that. Whenever appropriate, share this analysis in group or one on one conversations, social media, letters to the editor, blog posts, comments on websites, and anywhere else relevant. If you engage in or support civil disobedience, talk with activists on the front lines and with visitors, and broadcast the strategy in press releases and public statements. Though aboveground actions are likely limited to attrition, leverage their visibility to encourage escalation towards cascading failure. Please help Stop Fossil Fuels get this analysis out by sharing our site with others and distributing printed material.Mainstream media will never promote stopping fossil fuels. A grassroots of activists and citizens must spread knowledge of effective strategy and tactics.

Aboveground activists use legal tactics, plus civil disobedience. They work openly and publicly, often drawing maximum attention to their actions. Underground activists operate illegally, keeping a low profile. To stay off the radar of law enforcement, they can’t safely participate in aboveground activism, or even associate with aboveground members. Publicly exposing one’s convictions and willingness to break the law, or associating with such activists, makes one a target for investigations into underground actions. For example, private security firm TigerSwan surveilled dozens of known protestors following sabotage of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The company quickly fingered the two women who eventually claimed responsibility, suspects due to their history of civil disobedience against DAPL and other hazards.There must be a strict firewall between those working aboveground and those underground. The movement needs people on both paths, but they’ll have very different roles and organizing methods.

Aboveground involvement doesn’t rule out future underground work, but does increase the risk. Before publicly supporting ecosabotage, carrying out civil disobedience, or joining a radical aboveground group, activists should carefully consider whether they may ever want to work underground. Since those working belowground can use much more effective tactics than can those aboveground, activists should spend as much time as they need to make a careful decision, not jumping into aboveground work simply because it’s an easy or obvious path. While considering their choice, they should keep a low profile, sharing their deliberations only with fully trusted friends and family, and anonymizing related web browsing and posting.Your first choice is your most important: will you work aboveground or underground? Underground activists can and should protect themselves from the start.

Even if you don’t have a pressing need to protect your online activity, normalizing privacy assists activists who do. If only those with “something to hide” secure their data, their activity will draw suspicion. As more people use digital security tools, underground activists will better blend into the crowd. Prism Break provides a comprehensive list of available tools, and Freedom of the Press Foundation has links to many guides. Important concepts are: Free tools with which to start:Activists, especially those considering underground action, should use digital security tools for anonymity and encryption of communication.

The first line of defense is the firewall between aboveground and underground activists and groups. Law enforcement routinely investigates and surveils aboveground protesters and their associates. Underground activists must maintain distance from the aboveground to stay off law enforcement radar. Share information on a “need to know” basis. Only those directly involved should know about illegal activities or the people committing them. Others should neither ask, talk, nor speculate about illegal activity or underground individuals and groups. Activist cultures should ingrain a code of silence. Whether you’re aboveground, belowground, or completely uninvolved in the movement, never speak to law enforcement agents about investigations. Know your rights, politely say you don’t want to talk with them, then end the conversation. Carelessness is dangerous to activists, but so is paranoia. Establish behavioral norms within your group, and procedures for dealing with disruptive transgressions including sexism, racism, abuse, creation of conflict and division, and violations of firewall or “need to know” boundaries. It doesn’t matter whether or not someone is an infiltrator; the group must simply address and end problematic behavior. Those taking underground action must intensively study operational security, and carefully design and implement countermeasures to expected adversaries.Security culture is more important than any technical tools. All activists should learn these simple yet powerful guidelines.

Unfortunately, there’s no simple way to find and support activism against critical infrastructure. The movement isn’t organized about tracking and coordinating such work, so you’ll need to ask around or search online to find groups and campaigns, then research their effectiveness at stopping fossil fuels. (A useful movement support role for someone who can’t be on the front lines would be to organize and keep up-to-date information on active campaigns and their needs. The Environmental Justice Atlas may be a good resource with which to start.) Solo underground activists can carry out some useful actions on their own. Joining with even one or two others allows for more sophisticated and effective actions, but finding them may be difficult. Crimethinc offers useful considerations: Be conscious of how long you’ve known people, how far back their involvement in your community and their lives outside of it can be traced, and what others’ experiences with them have been. The friends you grew up with, if you still have any of them in your life, may be the best companions for direct action, as you are familiar with their strengths and weaknesses and the ways they handle pressure—and you know for a fact they are who they say they are. Make sure only to trust your safety and the safety of your projects to level-headed folks who share the same priorities and commitments and have nothing to prove. In the long term, strive to build up a community of people with long-standing friendships and experience acting together, with ties to other such communities.If you can serve on the front lines, the movement needs you.

We aim to support effective action by researching bottlenecks and vulnerabilities of infrastructure critical to fossil fuels, and disseminating our analysis and strategy to those who may take action. If you enjoy researching, writing, or outreach, visit our “Help Wanted” page and get in touch!If you can help with researching or with spreading our analysis, please join Stop Fossil Fuels in our work.

If you aren’t as organized, efficient, and productive as you could be, invest the time to find a productivity system which works for you. The payoff can be impressive for individuals, and even more dramatic for a group. With members consistently responsible for their tasks and obligations, and able to trust each other to do what they say they’ll do, group efficiency increases synergistically. Resources and systems abound, but good starting points are:Just as we must learn from military strategy, we should draw on lessons from the business world to maximize our personal & organizational effectiveness.